Note: I started to write this around 6:30pm on Election Day. I’d heard no news since 1pm, nor would I read any until morning. This is not an official statement, only a brief record.

8:00am

I drove with my wife and kids to town hall. We parked across the street in the church parking lot, in front of which sat a pickup truck, its bed occupied by a four foot high model of the church. It was by far my favorite float, back on July 6, when the town hosted its 250th anniversary parade.

Inside town hall, we greeted the volunteers at the first table, who sent us to the two poll workers, both of them public history people who live in my community. I took the paper ballot and found a stall, where I filled out my votes with my son standing next to me. As we left the building, we thanked the people working there.

Ours is a small town, and saw familiar faces as we walked back to the parking lot, stopping to say hello before getting back in the car. As I began to pull onto the road toward the kids’ school, we spotted another family we know. I rolled down the passenger side windows so we could wave. Then I made a left and heard my wife say, “Don’t run over the sign!”

Too late. I ran over the “Vote Here” sign.

Our friends hooted as the mom picked up the sign, which had broken in half. I yelled back an apology, but we were late for drop off.

When we returned to town hall five minutes later, the crime scene was cleared. As I entered, one of the volunteers appeared with the newly taped-up sign.

“That was me, I’m so sorry,” said I.

“Oh, it’s fine!”

We joked about this unfortunate disturbance at the polls before walking back out to the curb. The sign was placed along a rock wall, its hand-written replacement now positioned in the middle of the road.

“I was nervous!” I said to the family from earlier. We all laughed at me.

10:00am

My wife and I decided to hike up a nearby hill that is maintained by a local land trust. As you ascend, the far side of the ravine—a “gutter” in local parlance—grows into rocky cliffs. We’d reached the top where the path flattens out and began our descent down the other side, when a woman came walking toward us. As she neared, she slowed down and spoke softly.

“I walk this trail almost every day, and I just saw a moose for the first time.” We congratulated her, neither of us having ever seen a wild moose. We lowered our voices and I tried to keep my keys from jingling.

About 5 minutes later, we saw it.

Standing off the path about 30 feet from us, the moose had skinny, tentative legs, but two mountains for chest and head. It was gangly, without horns, either a juvenile or an older female, we couldn’t be sure. It stood for a moment to appraise us. Perhaps it was getting used to this world; then, too, it may have been wary from experience. When it began striding away, the moose moved magically, like a basketball player, a graceful veteran center.

We stopped to watch it cross the road and disappear again into the woods.

3:00pm

Back at home, I called my uncle. A radio talk show host in Denver for forty years, he said he had no idea what would happen today; I agreed with him.

I told him about my trip to Oklahoma City in September; he had never been. I described my visit to the Oklahoma City National Memorial Museum.

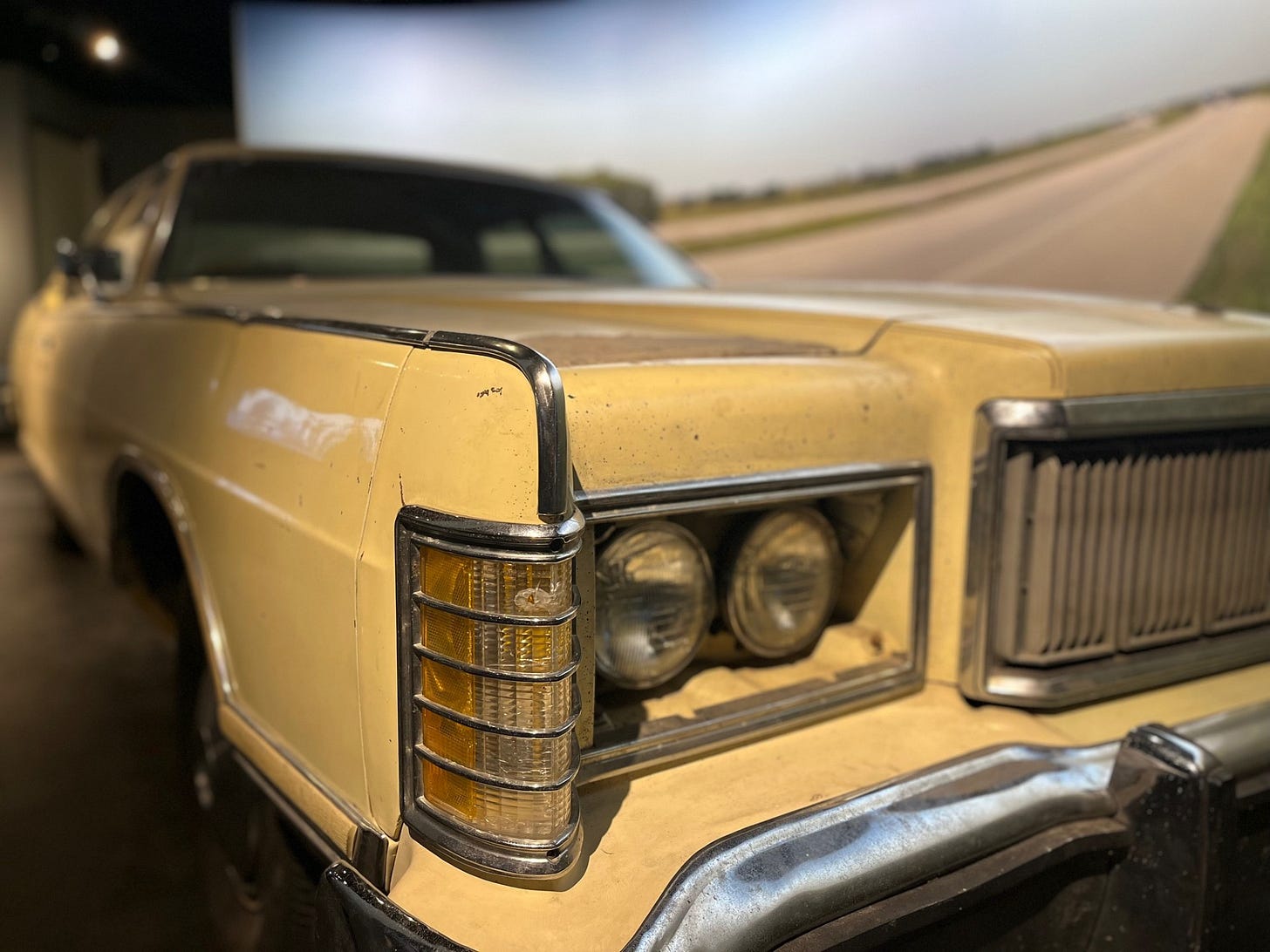

The Mercury sedan driven by Timothy McVeigh, I told my uncle, sits in a tight gallery space, an image of the prairie sky spread out on the driver’s side. To the visitor’s right, a glass case holds a barrel found at the farm of McVeigh’s accomplice, Terry Nichols. The two men mixed explosives in barrels like these, the same explosives used to bomb the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995, and take the lives of 168 people.

That museum visit left me numb because, rather than a collection of items from the past, the story told by the artifacts—piles of dust, a hotel sign, court documents—seemed alive and present. The story of America began and continues to center on the violence of men willing to destroy the lives of innocent people to protect the promise of unfettered liberty they perceive as their fundamental right. None of this got better after McVeigh; it has gone on for so long.

My uncle had covered the trial, which was moved to Denver, much to the dismay of the victims’ families. He saw McVeigh in person and described him as a “big, rawboned kid from Buffalo” who looked like someone we’d know from back home. My uncle knew people who were in the room when McVeigh was executed.

McVeigh drew inspiration from The Turner Diaries, a copy of which I saw at the museum. That novel, my uncle said, was also the inspiration for the murder of his colleague Alan Berg by neo-Nazis in 1984.

Then my uncle had to go prepare for his election coverage show.

9:00pm

We’d just put the kids to bed and turned the lights off when the phone rang. I saw it was my dad down in Florida, so I got up and called him back.

He shared the latest from the election. He lives on the Gulf Coast, less than 10 miles from where Hurricane Milton made landfall last month. As the storm crossed the state, there was a period of about 48 hours when I had no way to reach him. Luckily, he emerged unscathed.

In the aftermath, he’d driven his truck past drifts of sand three stories high on a main street, seen fishing boats that came to rest on highway overpasses, barrier islands scraped clean. I told him that was what I remembered about the Lower Ninth Ward and the lakefront in post-Katrina New Orleans: the sense of unreality-come-to-life, the experience of seeing things you had not believed to be physically possible.

The pile of debris in his yard was still there two weeks later, my dad said, still hadn’t been picked up. I cautioned that it was too early to call the election, though I hadn’t been watching the news. We said goodnight.

6:30am Wednesday

I woke up and read the election results with my wife.

Aftermath

Much more will be written and said about Tuesday, most of it flowing into the vast digital stream of information with which the nation flails and gasps and bludgeons itself. I hope to find the words for how I feel and where to begin.

For now, my intention is only to share what I experienced and the people I spoke with as the day unfolded, so that I can remember what happened.