We walked along the fortress walls as the sun began to set. My kids were determined to see the herd of feral cats that call El Morro home. The cats emerged drowsily from rocks and weeds, eyed by lizards and uninterested in our attention. Their numbers dwindled as we reached the ocean.

Castillo San Felipe del Morro, aka El Morro, is huge, medieval in scale and purpose. Begun by the Spanish in 1540 when the occupiers of Puerto Rico realized there would be competition for this island, the fortress looks out on the Bay of San Juan. Staring down from 140 feet at the crashing surf and jagged rocks, you feel the intended menace. This is the entrance to the Caribbean, say the massive walls, and the Caribbean belongs to the empire.

Our walk led us to a narrowing path with dramatic promontories. At a trailhead, we came upon a National Park Service sign titled “The Challenges of Climate Change.” The trail, it said, was designed in 2015 for visitors to reach the coast line. Due to sea level rise and erosion, part of the trail was now closed.

“Climate change is a real threat to park resources. The effects of erosion and seal level rise have been most notable since 2011 when a landslide near the north side of Castillo San Felipe del Morro affected the fortification directly, and emergency actions were taken to mitigate the threat.”

Subsequent landslides caused the collapse of a historic wall near the former gunpowder magazine.

There, I thought, is the colonialist project soup to nuts. The fort erected by invaders begins its melt back into the sea due to the prolific destructiveness of the invaders’ heirs. Conquest at the start, rising waves at the end. Before the fortress falls, of course, the sign itself will need to go because it contradicts the stories the empire tells us about their achievements and the future. The menace is now under threat. To speak of this—that, too, is a threat.

Holyoke brought us to Puerto Rico. With Mass Humanities opening its offices in the city, I wanted to know more about the places and cultures that shape the lives of many Holyoke residents. I also wanted a break from winter and bad news.

What I learned is that I love Puerto Rico. The island is beautiful and defiant, fighting to protect its identity and land as, yet again, outside forces seek to treat it as a blank slate. Its story is vital to understanding the Atlantic world and to anyone interested in the United States. While there, I learned from conversations with my great colleague Sonya Maretti, executive director of Humanidades Puerto Rico; with Marina Reyes Franco, curator at MAC Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico; with Tito “Sixto” Ayala at the Artesanias Castor Ayala in Loiza; and with Carlos Ruben at the Coliseo Angel Cholo Espada for Salinas, the sister city of Holyoke. Puerto Rico is also complicated and evolving, and this was the first of what we hope will be many more trips.

We visited El Morro on our last night. Afterwards, we walked the streets of Old San Juan. Ducking into the doorway of an art gallery, we heard the strains of AC/DC’s “TNT,” which immediately piqued my son’s interest. Inside, the walls were lined with brightly colored paintings of sports figures, musicians, and other icons of Puerto Rican culture. Josean Emanuelli, the gallery owner and painter, stood before a campus where a portrait of Roberto Clemente was taking shape.

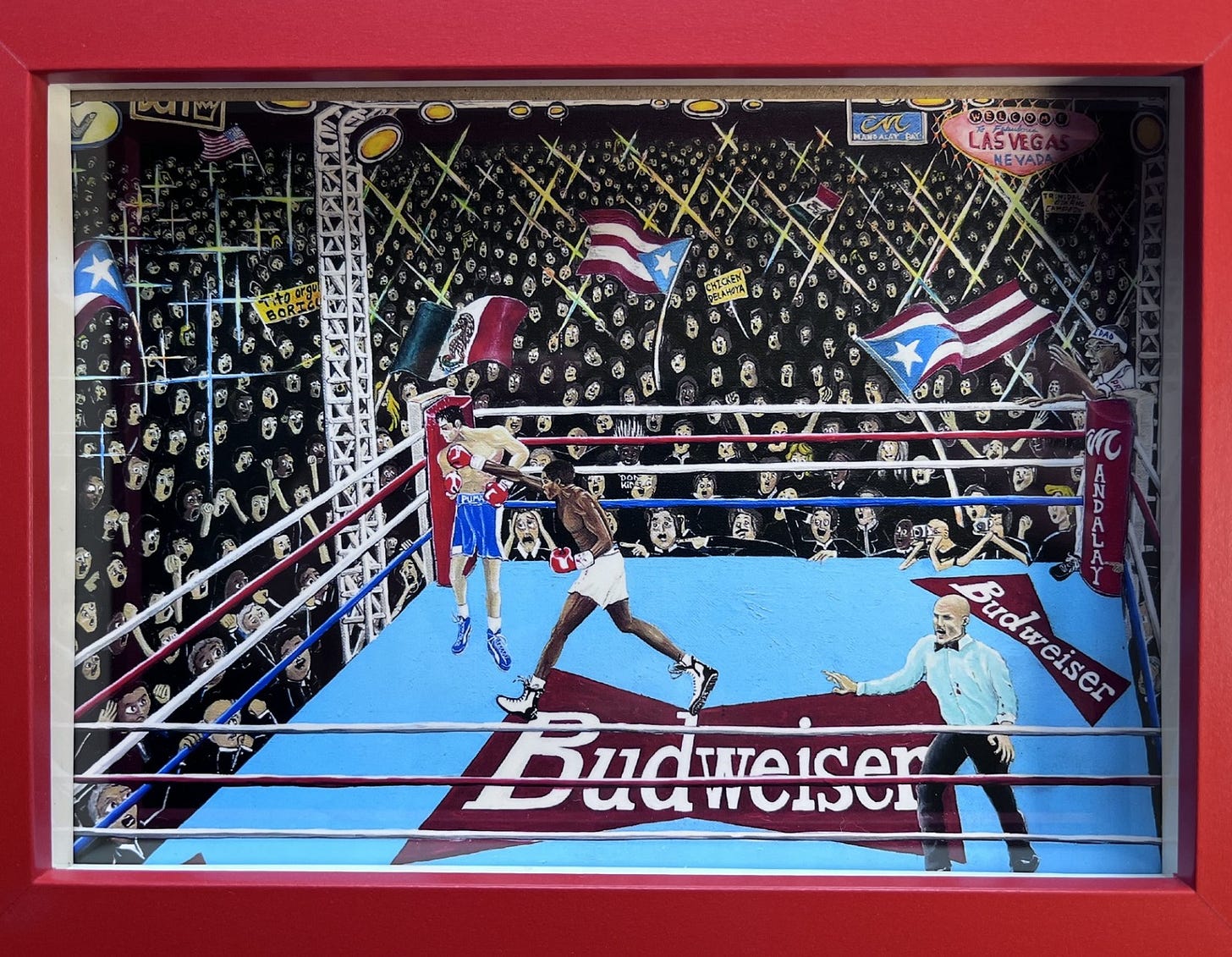

One painting caught my eye. It depicts a boxing match. The arena is full. Fans wave Puerto Rican flags. One fighter steps forward, his fist twisting his opponent’s face. You can almost hear the roar.

There were different sized prints available. I brought one over to Emanuelli.

“Which fight is this?”

“Felix Trinidad y Oscar De La Hoya.”

I laughed, I remembered. I’d forgotten that Trinidad was Puerto Rican, but I know I was rooting for him against De La Hoya, the “Golden Boy” Mexican-American with teen idol looks who won the lightweight title at the 1992 Olympics. Taking place on Sept. 18, 1999, Trinidad-De La Hoya was billed as “The Fight of the Millennium.”

I told my wife and she remembered that night, too, because we drove around New Orleans for hours trying to find a bar that was showing the fight on pay-per-view. It was worth it: both men rose to the occasion, Trinidad won a decision.

I grew up in a family that loved boxing. We cheered for Marvin Hagler over Sugar Ray Leonard, hosted parties in our basement to watch big fights, and felt cheated when the judges got it wrong. As with the NFL, the violence and corporatization eventually made me switch the channel, but I still hold good memories of the anticipation and comradery we felt while rooting for a side, a clear outcome. I bought two small prints, one for me and one for my dad.

The paintings were super affordable, so I selected a second. This one was from the perspective of a DJ, their hands hovering over two turntables. The vast lawn atop El Morro spreads out before them, filled with people dancing in a triumphant rave under a giant moon. A Puerto Rican flag waves from atop the fortress

What about this one, I asked Emanuelli, when did this happen?

Oh, he said, it never actually happened. There are parties like this, he knew, on beaches and in tunnels and at festivals. There has never, however, been one on the grassy plain of El Morro.

Maybe someday, he hoped.

Maybe you feel afraid like I do. Maybe you fear that the last two months held only the first swift steps into darkness. Maybe none of this seems reversible, extinguishable. You may feel let down, confused, or confirmed. The application of logic leads you to despair, planning feel irrelevant and naïve. The grasping speculation reminds you of the first weeks of the pandemic. There seems to be no alternative narrative you can follow towards hopeful options.

And yet those paintings spoke to me. One evokes a fight, the other a dream. I know that, at least for now, I am privileged to travel, to hold fond memories, to buy gifts, and that I will need to sacrifice in order to sustain. I know that we will need to find the will to fight, to dream.

To do this, we will need artists of all forms and spirits. We will need paintings and music. We will need to wave goodbye to the fortresses without losing our footing. Sitting next to me at home, these small paintings remind me to take a few steps forward in the ring or across the dancefloor. They say: We cannot stand still.