Douglass, the 4th of July and Solidarity

Lessons from abolitionist history and a statewide humanities movement.

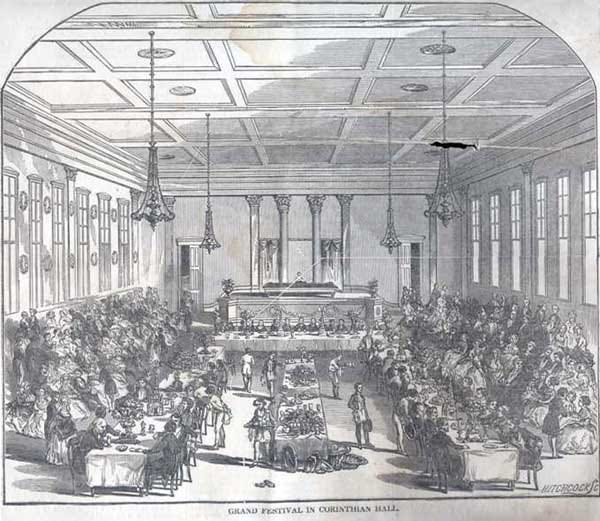

When Frederick Douglass entered Corinthinan Hall in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852, his career was at a crossroads.

Two months earlier, the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) took place in that same hall in Rochester. The occasion laid bare the growing divide in the abolitionist movement. Douglass had broken with William Lloyd Garrison and the leadership of AASS, and there was hell to pay.

The split with Garrison came when Douglass adopted an interpretation of the Constitution (and thus voting and participation in the electoral process) as a tool to be “wielded on behalf of emancipation.” Garrison believed that the document was fundamentally pro-slavery, and AASS members adhered to a policy of non-voting. The dispute over theory and tactics became personal, bringing to the surface the simmering jealousies and prejudices within the movement.

Garrison and his followers cast doubt on Douglass’s ability to come to his conclusion on his own, suggesting he had accepted bribes and could not be trusted. Gossip about his private life flowed freely. At the AASS meeting, speakers lobbed accusations of disloyalty, infidelity, and greed at a formerly enslaved man who had worked tirelessly for the organization.

It is important that we remember that context as we celebrate his legacy. Douglass carried these experiences with him as he took the lectern to deliver “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society.

June 23, 2023 unveiling of Douglass statue and Abolition Park, New Bedford Light

Responding to a statewide humanities movement

This week, communities around Massachusetts will read and discuss that speech at public events supported by Mass Humanities. Our grants will fund 41 readings this year, nearly double the number held in 2022. The list of events is remarkable in its geographic sweep and in the range of host organizations, from community development corporations to historical societies to activist organizations.

Shared readings of “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” are a tradition rooted in Black communities. Mass Humanities joined this movement in 2009, following the election of President Barack Obama, in a time when boasts of a “post-racial society” seemed hasty and ahistorical. Interest in the events grew in 2020 and 2021, following the murder of George Floyd and new calls for racial equality. The establishment of the Juneteenth federal holiday created more opportunities for residents to gather and reckon with history. People were looking for new ways to participate, and new leaders and new partners continue to take up the speech.

RFDT video, 2019. Directed by Amanda Kowalski, produced by Mass Humanities.

This statewide movement shares a common text, but each of our program partners decides on their own format, tailoring the event to the location and the needs of their audiences. This unique flexibility makes Reading Frederick Douglass Together (RFDT) a uniquely public humanities initiative.

Throughout this growth spurt, we at Mass Humanities thought a lot about the direction of the initiative. We wanted to support more readings, and we felt that reading Frederick Douglass was not a substitute for justice—it was a step towards it. We didn’t want to restrict the ingenuity of individual organizations, and we believed that inclusion meant more than distributing a press release.

In 2023, under the leadership of my colleague, Dr. Latoya Bosworth, we made several important changes to RFDT, all of them aimed at providing resources for bringing communities together.

First, we made funding for RFDT events available on a rolling basis, with streamlined applications accepted each month from January through May. As a result, we see events in February for Black History Month, and at other times in the year when a reading of the speech can fit into a larger event or effort.

In recent years, we heard from organizations interested in networking with other RFDT hosts. Dr. Bosworth led online events with local elected officials, historians, and the directors of past RFDT events. In this way, we sought to reinvigorate the discussion around Douglass’s relevance on a range of issues. We also convened workshops for our partners on facilitating discussions and conducting outreach.

RFDT event led by Clemente Course graduate Judith Foster.

We believed there was more to learn about the tradition of reading the speech, and that more awareness of Douglass’s time in Massachusetts could spark more readings. We recently awarded two fellowships made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities, one for a study of the shared reading tradition, the other for new research into Douglass’s tours of the Commonwealth. We hope that towns were Douglass once spoke will find new inspiration to organize future RFDT events.

There are many ways to facilitate conversations about Frederick Douglass, race, and democracy; in 2023, there are many more people coming together to do so. Each of us brings different experiences to a challenging, at times graphic speech. This year, we published a new guide on leading trauma-informed discussions, including ways to prepare audiences and provide them with exit strategies when the speech feels traumatic.

We also know that acts of intimidation are on the rise, so our new guides include proactive tips and strategies to maintain safety and security at the events. We believe in creating and uplifting safe spaces for these conversations.

The humanities belong on the street corner and in the classroom, at town meetings and at family gatherings. As a foundation, we strive to provide scaffolding that welcomes many perspectives to those intersections. This feels especially necessary given the pressures we all face in sustaining our efforts to build a more equitable Massachusetts.

2022 full reading of speech by Massachusetts thought leaders. Produced by HEARD Strategy and Mass Humanities.

“Oppression makes a wise man mad.”

Throughout 1851 and 1852, Douglass was constantly on the verge of mental and physical collapse. He faced the betrayals of former allies along with the burden of supporting his family and publishing his own newspaper.

At the center of this storm, he delivered a monumental work. In a nation where the Fugitive Slave Act was law. In a city where his own friends promised to “crush” him. In a room full of white people to whom he directed the rhetorical question, “Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?”

These circumstances make the 4th of July speech even more astonishing. They also call on us to do more than simply read the speech again this summer, because our own circumstances are so troubled.

This statewide movement to read Douglass unfolds in a time of book banning, public displays of intolerance, and the threat of political violence. We see the momentum building in many states for the erasure of Black history from classrooms and libraries. Massachusetts is not exempt from this ominous momentum.

How do we respond to these challenges? Since 2020, many organizations, corporations and individuals made commitments to justice and equality. This ranged to new hiring policies to legislation to advertising campaigns. Now, as we move past the restrictions, it feels necessary to check in on our promises. Are we committed to supporting leaders of color for the long haul? As retrenchment and reaction proliferate, where are the opportunities for people to stand together? What might drive us apart?

At an RFDT event, people stand shoulder to shoulder in a public setting, and they try.

They try to reckon with the nation’s history, not bury it along with any hope for the future. They choose to listen to each other recite the words of a man who found freedom in Massachusetts. These events have never been just about a historical text—they have always been opportunities to bring us together so we can, as Douglass instructs, “to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and the future.”

The story of the Garrisonians’ attacks on Douglass resonates with me this year because I see the seeds of solidarity in the RFDT events, and I want that solidarity to grow. I believe that can only happen when we work proactively towards the safety, perspectives, and power of participants, especially Black residents. This intentionality should be part of every public humanities engagement.

We in Massachusetts may see ourselves as carrying forward in the footsteps of the abolitionists, but we must learn from the movement’s failings as much as its triumph. I’m hopeful because of the hard work our team and our partners have done in advance of this year’s Douglass events.

I hope that when you attend a RFDT event this year, you meet someone new. I hope you find ways to support the RFDT organizations far beyond the day of the event. I hope you make connections with people in your town or city who share your interest in reckoning with history, and that you listen to the differences in their interpretations of the speech and of the nation. Listening is just as much a part of these annual gatherings as reading.

Send me an email and let me know what you learn.

Douglass ends his 4th of July speech with a verse from Garrison. At many of our RFDT events, the audience reads these final lines in unison:

God speed the day when human blood

Shall cease to flow!

In every clime be understood,

The claims of human brotherhood,

And each return for evil, good,

Not blow for blow;

That day will come all feuds to end,

And change into a faithful friend

Each foe.