“The artist becomes the last champion of the individual mind against an intrusive society.”

John F. Kennedy, Amherst College, Oct. 26, 1963

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, I was working at Rockefeller Center. I will never forget looking down Fifth Avenue and seeing a dark cloud of smoke somewhere near the tip of the island. I still think about the day that unfolded as I joined the flow of people crossing the Queensborough Bridge, and what changed for me by the time I reached my sublet in Brooklyn.

I’d moved to New York four months earlier. It sounds silly now, but I felt protective of New York in the days that followed the attacks. In the famously boisterous city, people drifted on sidewalks and subway platforms in a ginger silence. Movement was limited and shock took many forms. Along with the few friends I had and the coworkers I barely knew, I mourned and commiserated and waited. When President Bush climbed the rubble with his megaphone, I understood the need to create a moment. I was conflicted, a part of me wishing for revenge, but increasingly worried about the kneejerk militarization of our emotions.

No one feels they know New York better than a twentysomething who’s been there for a few months; you think you’ve taken on the greatest challenge and earned the right to defend the Big Apple against America’s assumptions. The effort of politicians, country singers, and people outside the five boroughs to turn this diverse, messy, genuine place into a bloody shirt for every American to wave—I hated all that.

During the years following 9/11, Bush loomed large in my creative work. I caught a break when May Liu offered me a regular gig in the basement of M Shanghai, her Chinese bistro in Williamsburg. Along with the writer and photographer Edna Leshowitz, I started a monthly performance showcase with the timely name: “Tony Blair Presents.” It was not great branding, but it reflected our wish to satirize the men directing the war, men whose language (“Code Orange,” Donald Rumsfeld’s untruths) generated paranoia and ridicule. The experiences of post-9/11 America were running themes for the NYC-based musicians, activists, and writers we hosted in that cozy basement.

By the time of the 2004 presidential campaign, the catastrophe of the Iraq war was in full view. The false justifications for the invasion, the disastrous decision to disband the Iraqi army, and the photos from Abu Ghraib represented a brutal hubris that resulted in the deaths of innocent civilians and US troops. The privatization of war and the institutionalization of surveillance merged with many Bush officials’ business interests. Everything smelled of oil.

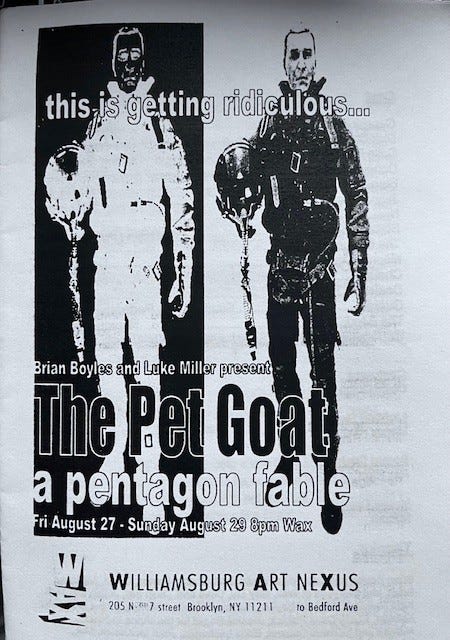

At the time, I was living with my hometown friend Luke Miller, a brilliant dancer and choreographer. We began to imagine a sort of carnivalesque revue that would mine the myths and misinformation of Bush and his cronies. Our friends at Williamsburg Art Nexus, a black box theater a block from the Bedford Avenue stop on the L train, agreed to give us three nights leading up to the Republican National Convention, which was due in New York on August 30.

Luke was and is the much more accomplished artist, a comic genius and the member of several touring companies. The show’s narrative—if you could call it that—emerged from my writing, but everything came to life because of Luke’s sense of stagecraft and his circle of performers. We scraped together funds, props and a tech crew to carry out a full hour of entertainment.

The Village Voice included the show in a special insert on “where to eat, drink, sleep, pee, protest—and hide out—during the Republican National Convention.” The guide lists more than fifty events ranging from comedy shows to film screenings to forums. Between the event listings, The Voice included short histories of past NYC protests, from the Bowery in 1849 to Crown Heights in 1991. Advertisements trumpeted everything from activist groups (Operation Truth, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Fair Share NYC) to drag shows to sales at Tower Records and sushi buffets. Flipping through these pages today, I glimpse the excitement of those days, when it seemed like everyone was coming up with a show or a party or a march to greet the president.

Among the audiences for these events: the NYPD. Chief Ray Kelly had led the Philadelphia police department’s crackdown on protestors during the 2000 RNC in that city, and had no hesitation about using the same heavy handed tactics. A 2007 New York Times investigation revealed the extent of the NYPD’s “RNC Intelligence Squad,” whose advance work included surveillance of “the views and plans of people who had no apparent intention of breaking the law.”

Under the umbrella of anti-terrorism, NYPD officers traveled the country in the months before the convention. “From Albuquerque to Montreal, San Francisco to Miami, undercover New York police officers attended meetings of political groups, posing as sympathizers or fellow activists.”

On the squad’s list: Billionaires for Bush, among the most visible sources of satire. A mix of pranksters and activists, they used guerilla street theater and chanted slogans including “Repeal the First Amendment,” and “Free the Forbes 400.” Their faux protests in 2004 were led by performers dressed in tuxedos and gowns who declared their support for corporations and insulted bystanders. Ahead of the convention, the Billionaires sensed something was afoot.

“It was a running joke that some of the new faces were 25- to 32-year-old males asking, ‘First name, last name?’” said Marco Ceglie, a member of the group. “Some people didn’t care; it bothered me and a couple of other leaders, but we didn’t want to make a big stink because we didn’t want to look paranoid.”

The paranoia was well founded. Marchers faced the brunt of the NYPD’s aggressive approach to free speech, with divide and conquer techniques applied by officers on motorcycles, mopeds, and horses. More than 1,800 people were arrested during the Convention. In 2014, the City of New York paid out nearly $18 million to settle hundreds of lawsuits that accused the police of unlawful arrests, detentions, and mistreatment of protestors.

We talk a lot about the hatred in our politics today, but menace and aggression were part and parcel of that earlier era. After 9/11, the Bush administration encouraged a politics of “with us or against us” that questioned the patriotism of its opposition. We were told to suspect everyone, particularly anyone Muslim. This felt particularly horrendous in New York, a place that remains the best version of the proverbial melting pot. Here we were living in the most diverse city in the country, long portrayed by outsiders as a dangerous freak show, being told that, because of the wounds we suffered and on behalf of all Americans, we should be on the lookout for our neighbors.

The consequence of the domestic War on Terror still shape our political discourse. The NYPD remains prone to violence in its efforts to quell protest. And while the attacks and the subsequent wars move farther from the center of our debate, those experiences remain fundamental to my understanding of the country and our problems.

So, too, does “The Pet Goat.”

In Brooklyn, we began to call in favors. We wanted performers whose style could to walk the line between laughter and tears. They also had to work for something close to free, plus pull it all together in two rehearsals. Twenty years later, I’m still in awe of that cast.

As they stood in line to enter, audience members were frisked by uniformed guards played by the groundbreaking Stanley Love Performance Group. A giant diesel-powered Mercedes sedan, driven by WAX co-founder David Tirosh, pulled into the garage doors of the lobby to disrupt the security. Tirosh stood behind a podium and gesticulated like a dictator to a soundscape designed by Ray Riga.

Inside the theater, the show began in darkness punctured by the glowing heart of Dick Cheney, strapped to the chest of my fellow East Village Radio DJ, the emcee Long Division (aka Dan Strauss). He was followed by playwright and director Antonio Rodriguez as Colin Powell and dancer Eric Russell as Rumsfeld. Our roommate Julian Barnett, a choreographer now on the faculty at the University of Vermont, played Bush, wearing a pilot’s jumpsuit in reference to the infamous declaration of the war’s end. The four sat down to play a silent game of poker, with WMDs, overthrown elections, and car bombs as their chips.

When they dispersed, burlesque stars Dirty Martini, Tigger, and The World Famous *BOB* played members of the Bush family, as did the gifted dancer Hilary Clark. Taylor Mac, who went on to receive a MacArthur Genius award, performed an original song, “My Lover Lives in Undisclosed Locations.” Costumes by David Quinn and lighting by Mandy Ringger gave everything a loud shimmer.

In the penultimate performance, Elyas Khan and Fred Wright of Nervous Cabaret performed “Page 13,” from the DUMBO-based band’s first album, Ecstatic Music for Savage Souls. The song includes excerpts from Waiting for Godot, like Gogo’s desperate question to Vladmir, “We’ve no rights anymore?”

As the last notes rang out, the rest of the cast emerged from the wings, each holding a piece of paper. Together with the audience, we read the First Amendment in unison.

Did it all work onstage? At times. Caricaturizing the Administration wasn’t novel, but the use of dance, live music, and burlesque, and particularly the level of talent involved, made it spectacular and touching and very New York 2004. Then and perhaps always, there was something incredibly apt about following Beckett with the Constitution.

The opening show almost collapsed in confusion, but the second night was quite good, so much so that it inspired a degree of overconfidence that led someone to break out the alcohol before the end of the third and final performance. The after-party was, of course, grand.

I learned a tremendous amount from “The Pet Goat,” including how little I knew about theater. It was a thrill to help organize an ensemble, something I went on to do for many years in different ways. The emotions, the begging, and the mental gymnastics of staging, the mistakes, high points and unexpected falls—those are part of making art. But the approach of the Convention gave it a purpose and a deadline. The city felt alive and we had the chance to express ourselves. The collective talent of this ad hoc group was quite a way to speak truth to power and towards a small audience of New Yorkers and people visiting New York.

As much as they resonate with me today, “The Pet Goat” and the RNC unfolded in a different world. This was pre-smart phones, at the first dawn of social media. No one took selfies in the lobby, there existed no event page or Facebook group. No videos were posted to YouTube, nor do I have any photos, digital or in print. We created the show using a twenty-century, largely analog approach to entertaining people who gathered physically and in close quarters.

That difference is everything. The election campaign unfolding around us this year is thoroughly based in the digital. Conventions, protests and performances unfold through platforms that were unavailable in 2004. Over the last twenty years, the world underwent a shocking revolution in how we process information. Protests still take place, art is still created in response to treachery. Most all of it is recorded digitally for distribution beyond the immediate participants. TikTok allows creator and audience alike very different forms of participation than the black box.

What remains from that show is a parched copy of the Village Voice, a few old programs, and a touch of doubt.

For all the laughter, I remember how the election ended. I would laugh again about the state of American politics, but less and less as the years went by. I wonder if satire was the right response from young Americans in the face of Iraqi civilians experiencing devastation. I wonder if pointing out the bawdy clothes of the emperor made any difference at all outside the 100 or so people who saw that show. Most everything bad that was happening before the RNC kept on happening.

Still, I don’t look at those artifacts and scoff or shake my head. These were the ways we had to contribute during a terrible time. People need cultural activities for protest, for expression, for letting off steam. We need to share the fear and worry, and we need opportunities to do this in person. Artists shoot flares in the darkness so that people can, by that light of art, see what surrounds them.

For a few days in the summer of 2004, I enjoyed what I saw.