Once upon a time, I took a sabbatical to join the circus.

For three months, I followed the preparations, unforgettable spectacle, and aftermath of the biggest show in America this side of a presidential election: the Super Bowl. It was quite an education.

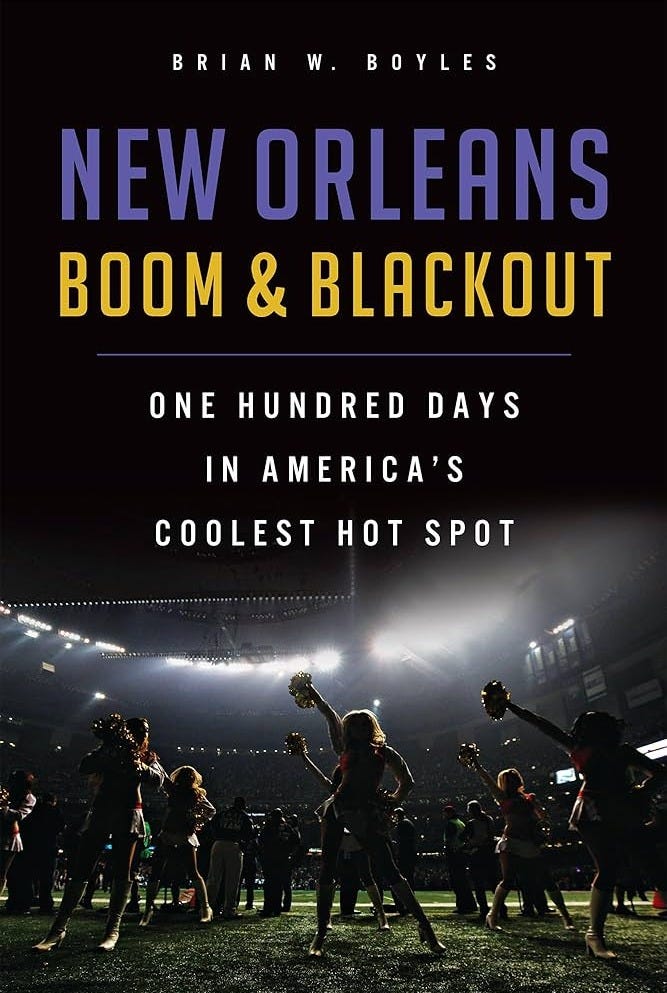

This Sunday, the Super Bowl will take place in New Orleans for the first time since 2013. My first book, New Orleans Boom and Blackout: 100 Days in America’s Coolest Hotspot, chronicled the events leading up to the 2013 game and the lives of local residents, including hospitality workers, politicians, artists, business owners, and activists. I spent twelve weeks riding the wave that preceded a game in which, famously, the lights went out just after halftime.

When the attack occurred on Bourbon Street last month, in the wee hours before the Sugar Bowl, my mind went to the people I knew who worked in the French Quarter, many of whom I met while writing this book. The excerpt below includes a description of that street at the same time of night, almost a dozen years ago, before another big game.

Boom and Blackout turned ten years old in January. You can order the book here or at your local bookstore.

Excerpt from Chapter 17: February 2 (One Day to Go) “I Am Your Great Time”

There were different tiers of access at the GQ party. Around 250 people with wristbands like mine mingled under a tent attached to the Elm’s Mansion on St. Charles Avenue. Luckier guests had access to the mansion, which I imagined was warmer and more intimate than the tent. Networking and texting blossomed in the growing crowd of sharply dressed young professionals, everyone talking loudly at the same time. Here were the connected out-of-town visitors, the people who worked for the sponsors, brands and teams that made the week into a giant, if more glamorous convention. Tonight was the last round for the big parties, and GQ had gone the extra mile: Lil Wayne was due on stage in a few minutes.

Standing next to a sleek new Mercedes, I met Mr. and Mrs. Mike Rubenstein of Rubenstein’s, the famed clothing store opened in 1924 at the corner of St. Charles and Canal. They were invited to the GQ party, Mr. Rubenstein told me, because the store sold Lacoste, one of the night’s brands. When their daughter called to ask how the party was, Mrs. Rubenstein moved further up in the crowd for a report, leaving Mr. Rubenstein and I there to converse and, I admit, for me to admire the gentleman’s clothes. He was my height and wore a blue jacket over a green shirt, striped tie and dark pants, along with simple wire-rimmed glasses. Despite my envy, Mr. Rubenstein was such a regular guy that we easily fell into conversation.

Business on Canal Street, he said, suffered during the streetcar construction, no doubt. They had a busy week for the Super Bowl, a lot of people in the store. We compared neighborhoods we lived in or used to live in. Mr. Rubenstein knew that Lil Wayne emerged from a group of other local rappers, and I credited Wayne’s industriousness and lyricism. Mr. Rubenstein said he used to see Fats Domino on Bourbon, along with Pete Fountain, Al Hirt and other local heroes; he even told me a dirty story about Pete Fountain. Surrounded by brands and out-of-town marketers, we talked as locals do, about legends and favorite corners.

Then the music grew loud, the DJ asked us yet again if we were ready and Lil Wayne burst forth to “If I Die Today,” a song with all the metallic apocalypse of today’s commercial rap. His verse closed with an updated version of the old “St. James Infirmary” request:

If I die today, remember me like John Lennon

Buried in Louis [Vuitton], I’m talking all brown linen, huh

When the track cut, he greeted us.

“How y’all doin’ tonight? My name is Dwayne Carter. You can call me Lil Wayne or you can call me Tunechi. I am from this great place you are at right now, New Orleans, Lil-weezy-ana. If you’re not from here, make some noise. If you’re glad to be here, make some noise. What team you going for?” People called out names.

“Before I get started, I must let you know three important things about myself. One is I believe in God. Number two is, I ain’t sh*t without you. And the most important is, I ain’t sh*t without you, seriously. If you came to have a good time, say, ‘Hell yeah.’” Hell yeah. “If you here to have a great f*cking time, say, ‘Hell yeah.’” Hell yeah. “Well, ladies and gentlemen, I am your great time. Let’s go.”

The GQ party turned into a forest of raised arms. No one pushed or danced. These were stylish adults with an open bar and connections, partygoers who could restrain their emotions. But Instagram the moment? Without a doubt. You couldn’t play off being in the same room as Lil Wayne as no big deal. Lil Wayne, from New Orleans, was as A-list as they came in 2013.

Mr. Rubenstein and his wife were slightly amused, and certainly not put off by all the cursing and bombast. They were New Orleanians, too, who ran a family business across Canal Street from Bourbon Street; they’d seen circuses before. When Wayne’s set finished after thirty minutes, I wished them both well and stepped to the bar for a bottle of the newly debuted Beck’s Sapphire.

It was almost 3:00 a.m. when I returned to the Quarter. Outside the Bienville Street entrance to the Olde N’awlins Cookery, a mountain range of garbage bags hugged the curb as cooks and dishwashers smoked cigarettes and watched the stumbling parade pass on Bourbon Street. Cups, beads and soggy cardboard filled the gutters along Bourbon. A young man in a white sweatshirt stomped through a knee-deep patch of the filth, mumbling loudly that he was “a grown man.” Teenage boys with ten-thousand-yard stares hugged girls who sucked on lollipops. Groups gathered amid the procession to flirt and share drinks, the famous street their own unsupervised mall. This was common in the early morning hours, when the street grew younger and, it seemed, more local. In the wee hours, the Super Bowl gave way to the status quo.

Confused but seemingly concerned, a bum with a long beard sat against the Sheraton and contemplated his hand. An EMS vehicle had parked in the middle of the 500 block. The friends of whoever was inside argued with the paramedics. “She’s okay, she’s okay,” they insisted. Finally, a woman stepped down from the rear door on wobbly stilettos into the arms of her comrades. The navy blue EMS vehicle was not a traditional ambulance, but smaller, with a sleek cab. It looked like the perfect French Quarter rescue capsule.

In the hierarchy of tourist destinations—the Superdome, Jackson Square, the streetcars—everywhere else took second place to Bourbon Street. Bourbon Street was ensconced deep within the genes of the New Orleans brand. Master plans could plot new “demand spaces,” but Bourbon was the city’s Eiffel Tower, Millennium Park and Vegas Strip. Thousands worked there, millions visited and, in contemporary America, nothing truly compared to it. At 3:00 a.m. on the morning of the Super Bowl, Bourbon Street was filled with teenagers sipping vodka from the bottle and serviced by emergency vehicles that allowed injured patrons to walk out the back door. New Orleans had much to offer its visitors, but its most unique offering was a strip of land where you could drink in all-night bars or on the street until the sun came up. Conceivably, you could run into anyone from your past on Bourbon, your elementary school teachers, old flames or distant cousins—people from every level and locale passed through for a hand grenade or a hurricane. Wolves lurked on the side streets, ready to rob or proposition a boozy Minnesotan. The police stood sentry to make sure everything stayed on track, but they weren’t sticking their hands in unless something was on fire; many times they were too late. People didn’t get hit over the head inside Disney World, but on New Orleans’ main tourist thoroughfare, you had to be careful.

At Rick’s Saloon, DJ John Amos had dancers on both stages. It was now 4:00 a.m. The room was packed with men and twice as many dancers as usual, some perched on men’s laps, others who prowled back and forth. I took a stool at the front bar, where a dancer soon joined me. She had grown up in St. Bernard Parish, but her family recently moved to Slidell, where, we joked, everyone was scared of the immigrants from the parish. The women working tonight were more beautiful than usual, she observed. They came in for the game.

An hour later, I walked off Bourbon. On St. Peter Street, a green garbage truck crawled from door to door. One worker grabbed a plastic bin with the company’s name, Progressive, and slid it in front of the great maw in the truck’s rear. A second worker positioned the bin on a lift attached to the truck and then guided the bin as the lift flipped it over, depositing its contents into the truck’s teeth. As the bin tilted upside down, the second worker expertly dodged a rivulet of fluid. When all the trash was emptied, he pushed the bin back toward the curb, where the first man waited to trade him another bin of trash.

After one hundred days pondering the new New Orleans, I paused to watch the truck move along the poorly lit side street, methodically going about the upkeep of the golden goose. The cycle hadn’t changed so much: New Orleans welcomed the big games, allowed the fans and corporate sponsors to run wild and then cleaned up the mess. Many different jobs existed within that cycle, with trash collector among the lowest and most crucial. The next party was impossible if tonight’s garbage wasn’t picked up, and in this new era, there were more parties than ever, so more trash collectors were needed. The supply chain of the new New Orleans might begin when a visitor arrived in a sparkling airport named after Louis Armstrong, but eventually it dwindled down to a couple men hoisting garbage cans into a truck labeled Progressive at 5:00 a.m.

For the first time in my life, I hailed a pedicab. The driver had shoulder-length hair and acne brushstrokes on either cheek. As we pulled away, he stood up to peddle, his beautiful head bobbing up and down against the pale sky. His name was Mitchell, he was nineteen and he had arrived from Chicago in September.

“What do you think?” I asked him.

“I love it,” he said with wonder.

How else would he feel? He had cash in his pocket and a job in the French Quarter that allowed him to sleep in, only to reawake in a city that encouraged him to remain poised at the edge of adulthood, meeting people who needed rides and told him things and asked him questions. I was once that age in another New Orleans, but I knew what he felt. No one should love New Orleans more than Mitchell. The question would always be: did New Orleans love him back?

He deposited me in the parking lot of my office building in the Central Business District. I leaned against my car to watch the sun rise on Super Bowl Sunday.